Comedian Gary Gulman’s research to write Misfit: Growing Up Awkward In the ’80s, began almost 50 years ago. While most of us have hazy memories of kindergarten, Gulman’s are somehow in crisp focus. As years pass and lunch boxes and school bus drivers become wall-lockers and shopping malls, the author recreates the intensity of those lonely, befuddled days, giving readers grace for their own baffled adolescence. Everyone has been there.

“I’ve had a lot of practice for this,” Gulman tells The Daily Beast; he has been performing stand-up comedy for more than 30 years, including in his groundbreaking 2019 HBO special The Great Depresh. “I’m not the hero in my act. A lot of situations I bring up my failings or humiliations, and they’re based on my pride and irritability. It comes across as trying to make the world a little fairer, and usually just yelling at how unfair everything is.”

Turns out that good practice for writing about kindergarten through high school.

“I always thought of myself as someone who’d write a book, and I’ve found how important books have been to my life,” he says. From Philip Roth and Toni Morrison and Ray Bradbury to the subconscious inspiration of John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany, Gulman says, “They didn’t always explicitly say what you should know about life, but especially the second readings of books I’ve enjoyed, these authors in their sixties, seventies, eighties, they brought me wisdom.”

In Owen Meany, Irving’s narrative structure is an older man reflecting on the life of a long-dead friend—like many of Irving’s novels, bad luck and violence dog the characters. Misfit is kinder, both to Gulman and the striving children who made up his Massachusetts childhood. But kinder is not easier; memories are steel wool scraping on the heart. Blessed, or cursed, by a very good memory, Gulman said, “I knew as certain events were happening, that I would never forget, and I was fortunate in having that recollection.”

He writes the gamut of childhood experiences: well-meaning family choices that go very bad, ups and downs with friends who are there and then aren’t, sports and hobbies that give meaning to the day, better friends that stick it out, and romance that lingers, brief as it was.

“Every few years I’ll have a dream about my first girlfriend,” he says. And when he was younger, “I felt sort of ashamed I was pining about her. I remember a creative writing class in college, and the professor told us that we’d always remember our first girl or boyfriend, that he’d dreamed about her just the other night. It was the first time I knew someone who admitted that. I didn’t have to think, ‘Oh no, this will never end,’ It was wonderful that I don’t have to feel bad thinking about this thing.”

One of those things, for example, was “that girl,” Kristel, who Gulman shared class with during junior year, along with his friend Lori. He tried to flirt using beginner-level comedy to earn Kristel’s honest laughter.

While Misfit’s narration breaks the fourth wall quite a bit, it’s subtle. An older voice relates events, but not quite with Gulman’s adult perspective. That increases the impact when present-day Gulman’s frustration with 1980s-Gary becomes clear.

“I threw away this sentence toward Lori, ‘Ask that girl Kristel to go,” Gulman writes, as he and Lori arranged a summer movie excursion to the mall. He continues: “That girl. That’ll throw ’em off the track. ‘Ask that girl Kristel to go’ was an abridgement of the truth which was: ‘Ask that girl who I think is so lovely and nice…the girl who laughed so hard at my joke…the girl for whom I take a calculated route to seventh period…she smiled and my face was warm for the rest of the afternoon….That girl. I believe her name was Kristel.”

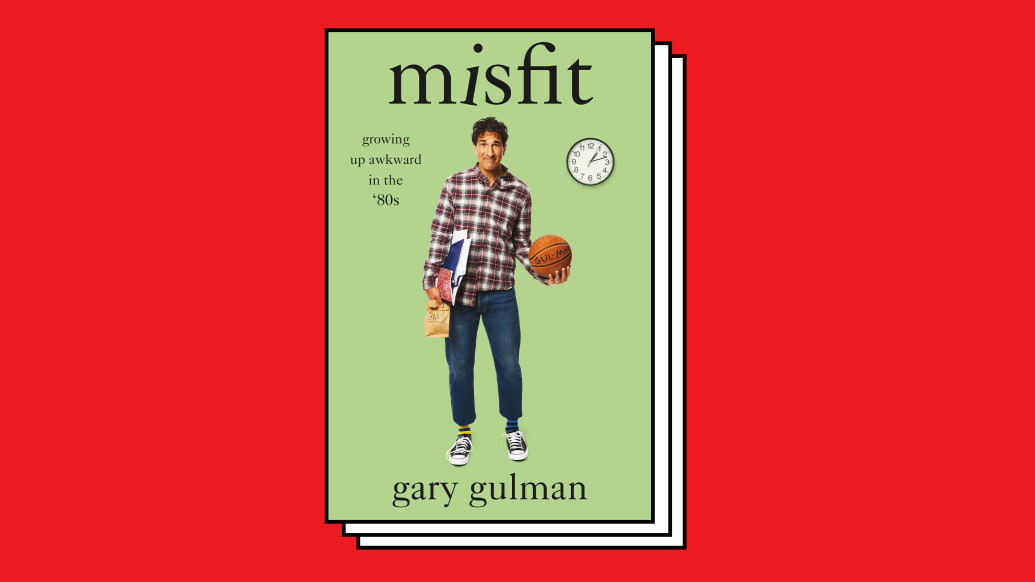

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Handout

It’s not the despair that is the risk to a 17-year-old, were the Kristel of your own memory to say no—this time, Kristel says yes—the despair is to be expected. It’s the hope that made it hard.

“This scene was this great thing,” he says, “where I had taken this small chance, asking ‘that girl’ to go out on this date, and it wasn’t a date, it was a group thing. I never would have called it a date.” The teenage love affair lasted “all the way to New Year’s Jewish New Year’s,” Gulman writes. “It ended October 4, 1987. It rained all day. I didn’t come out of my room.”

“From my brother Max, I received the following consolation: ‘Girls are fickle at that age. That’s why I never dated in high school,’” he continues. “Oh, that’s why.”

As Gulman showed again, the word “that” can do a lot of work.

Still, the story has a happy ending. Gulman, 53, now married to Sadé Tametria (“not that Sadé,” he often says on stage) has kept in touch with Kristel. She’s attended his shows, and he says it’s been a “great experience to tell her that she’s portrayed in a loving way in the book.” That resolution might be a little maudlin for cynics whose pining for lost love lacks similar closure. But they can work that out in their own stand-up careers.

Misfit’s vibe is like the movie A Christmas Story, with the young character’s narration told through mature language. Gulman uses “bathos,” a more grown-up version of logos, pathos, and ethos that barrage high school English students. Bathos can be poor writing, when an attempt at high drama falls flat, or it’s deliberate, often satirical, with a “bombastic, elevated style to describe something mundane and trivial,” Gulman explains.

Across three pages, Gulman describes ever-encroaching terror, reading The Monster at the End of This Book. In Gulman’s perspective of a 5-year-old, the book is “a riveting thriller from page 1. Nay, from the cover.” Gulman’s use of “nay” is an example of bathos. Spoiler alert: The “monster,” as any middle-class child of the 20th century should remember, is Grover, a kind-hearted Muppet. The book introduced children to the concept of dramatic tension.

Gulman employs nostalgic references, like Grover to ground Misfit in reality. “When I read, I want to see brand names,” Gulman said. “Like in the Kinks Lola, when he mentioned cherry cola, I felt like they were living in our universe.”

Brand names like Chuck Taylor sneakers, or Orange Julius at the mall, don’t have feelings to be hurt, but some real names and identifying characteristics have been changed. As for recollections, Gulman said that while he paraphrased conversations, he was confident in specific sentences.

When the NBC miniseries Holocaust premiered in 1978, Gulman writes that his second-grade friend Wally, “filled me in on what happened to Jews, sharing with me the unspeakable specifics. He said that Jews were burned alive in ovens and starved in camps…I think he enjoyed unnerving me. ‘Why?’ I asked. Without any hesitation Wally gave me his analysis. ‘The Jews were rich snobs…walking around with their noses in the air.’ Wally was pretty much the only friend I had in second grade. There just weren’t many worthy choices. Being friends was more habit than harmony.”

Gulman has seen Wally again over the years, and “he’s very contrite.”

The book’s young Gary is kind and gentle, dedicated, reflective and smart, and craven, a follower, sometimes a snide verbal bully who uses skill with language to target the kids who can’t think as quickly. He is surprised when a teacher gives him a warning for “‘the way you give nicknames and when you make the buzzing sound associated with…Richard Dawson’s Family Feud when someone gives the wrong answer.’ To me, this warning notice meant Mr. Mercier thought I was an insensitive, cruel little shit.”

To most readers, the book will be a mirror.

“There’s an OCD with my honesty. My mother was very sensitive, and she’d tell people half-truths to keep from upsetting people,” Gulman says. “My way of rebelling was to be more honest, especially about my shortcomings. I wish I had behaved better, been kinder, more thoughtful, and we cringe and try to forgive ourselves. My wife was able to give me that perspective many times, that you were just a child.”

On the page, that perspective is more drawn-out than a punchline in a stand-up act. One lengthy story covers Gulman’s evasion of ninth-grade bully Nunzio. Gulman’s snitched on Nunzio sneaking into the school’s basketball court, and he hears the threat “Nunzio’s aftah you.”

Fiction trains us to expect a payoff to confrontations with high school bullies, that tension of the 3 p.m. bell, a climactic throwdown. Real life is often just a beatdown, on tree-shaded backstreets lined by upscale homes unfamiliar with the sight of teenage blood. The punchline is the punch.

In this case? It’s a spoiler, but Nunzio barely cares. The final act is his bored “whydja tell” and all Gulman can muster is “I didn’t wanna get in trouble.” All the tension and fear, and that’s it?

“It’s a relatable thing to be afraid, but Nunzio’s story would not have worked on stage,” Gulman said. “Part of me was reluctant to include it in the book, but it occupied so much mental energy, how do I not talk about the thing that was the main takeaway from that ninth-grade year? I went out of my way to adjust my entire school schedule. I worried about a lot of things in my life and lot of things didn’t happen. I think that’s a common phenomenon. It’s a similar situation where someone popped their head in the wrong classroom and the rest of the day nobody thinks about it again, but it was the most embarrassing moment in that person’s life.”

In 2017, Gulman worked as a camp counselor in his recovery from depression, and told the Nunzio story to his fellow counselors. At 6 foot 6 inches, Gulman fits the stereotype of the bully, not the bullied, so it was a surprising revelation.

“It brought me much closer to everyone, and we all opened up about harrowing high school stories.” The workshopping also taught the value of the experience, even if it lacked a dramatic finale. On the printed page, the Nunzio anticlimax conveys the youthful struggle against fear that loomed large, especially if it now seems ridiculous. Misfit’s in-the-moment style relates how it felt, without snarky dismissal.

In stand-up comedy, success is predicated on the audience’s laughter. In Misfit, without the dead air of a silent crowd, Gulman says, “I could write sentences that I believe are funny and almost have an arrogance that you should think this is funny, and if not, that’s on you. I got to be a little more selfish on the page.”

Misfit’s childhood chapters are interspersed with accounts of Gulman’s on-going recovery from depression, which is the primary subject of The Great Depresh. He said the book contains no jokes from his act, and his current book tour is not a David Sedaris-style reading, but rather a way to add depth and context, without repeating stories.

“I have one eye on not being preachy,” he says. But at Misfit’s end, he does give a list of life lessons. Among them: “If you’re scared about something you’ve never done before, like reading, or multiplication, or dating? Say this: ‘I’ll figure it out.’ Then remind yourself of everything you’ve figured out so far.”

For more, listen to Gary Gulman on The Last Laugh podcast.

Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celeb News

247